Content

- Types of allergies to vaccines

- Clinical manifestations of vaccine allergy

- Allergy to vaccine components

- Can a person with allergies be given the vaccine?

- How to diagnose vaccine allergy?

- Procedure for vaccinating patients with vaccine allergies

- Bibliography

Vaccines play a huge role in preventing a range of bacterial and viral diseases, including COVID-19, the new viral infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 that has caused a global pandemic. A number of vaccines have been created against COVID-19 in Russia - Sputnik V, Sputnik Light, Kovivak, Epivaccorona, but people are often afraid of severe side effects, including allergies to vaccines. Severe allergic reactions to vaccines are rare but difficult to predict, and their existence significantly complicates the promotion of vaccination.

Prevention of viral hepatitis B in adults at home

The most reliable prevention is vaccination.

Since 2000, it has been administered to all children, starting at birth. And more recently, for adults too. Vaccines provide safe and reliable protection—tests show that 90 to 95% of vaccinations in healthy people result in resistance to hepatitis B. Hepatitis B vaccination is safe. Side effects are usually minor, most often soreness at the injection site.

A contraindication to vaccination is an allergy to any ingredients of the vaccine.

Types of allergies to vaccines

The World Allergy Organization has recommended that immunological reactions to drugs (including vaccines) be classified according to the time of onset of symptoms]. This system defines two main types of reactions: immediate and delayed. This approach is designed to distinguish immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated (type I immunological reactions), which cause many immediate reactions, from other types, since these reactions carry a risk of life-threatening anaphylaxis if the patient is reexposed.

- Immediate reactions begin within the first hour after administration and may occur within the first few minutes. IgE-mediated reactions are most likely during this time period.

- Delayed reactions appear several hours or days after administration. These reactions can be caused by several different mechanisms, but they are rarely due to IgE.

Clinical manifestations of vaccine allergy

An immediate, IgE-mediated allergic reaction may involve various combinations of up to 40 potential symptoms and signs.

The most common symptoms and signs:

- Skin symptoms including redness, itching, urticaria and angioedema.

- Respiratory symptoms including nasal discharge, nasal congestion, change in voice quality, feeling of throat closing or choking, stridor, cough, wheezing, and shortness of breath.

- Cardiovascular symptoms including syncope, syncope, mental status changes, palpitations, and hypotension. Anaphylaxis (anaphylactic shock after vaccination) is the most severe form of IgE-mediated allergic reaction.

Anaphylaxis

is defined as a systemic allergic reaction that develops rapidly and can lead to death. Anaphylactic reactions to vaccines are rare, with rates ranging from 0.65 to 1.31 per million vaccine doses administered in active surveillance studies.

Anaphylactic shock occurs most often within the first 30 minutes after the vaccine is administered, although the onset can sometimes be delayed up to several hours. Later onset reactions are usually less severe. Reactions that occur several hours or days after vaccine administration may be due to delayed absorption of the allergenic component. Some of these late reactions may be causally related not to the vaccination, but to another allergen that the person was exposed to after receiving the vaccine.

Reactions to the vaccine

. Not to be confused with complications after the administration of vaccines (post-vaccination complications, PVO). They can be both immunological and non-immunological in nature.

- Fever and increased body temperature are common after administration of a vaccine and do not interfere with the administration of subsequent doses of the same drug (booster, booster).

- Local reactions to vaccination, such as swelling and redness at the injection site, are common and resolve on their own. This should not be considered a reason not to receive further doses of the vaccine.

- Serum sickness and

-

like

include rash, fever, malaise, - Other rare reactions - delayed immunological reactions include rare cases of persistent itchy nodules at the injection site of aluminum-containing vaccines, which may be associated with delayed-type hypersensitivity to aluminum. Another rare reaction is encephalopathy. Some of these more serious reactions may contraindicate further doses of specific vaccines.

Local reactions can be treated with cool compresses during the first hours after symptoms appear, paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if pain or swelling is bothersome. However, antipyretics should not be given prophylactically, “just in case,” as several studies have shown that these drugs may reduce the immune response to vaccination.

joint tenderness or polyarthritis occurring one to two weeks after vaccination or sooner if the patient has received the vaccine more than once.

Vaccine administration may cause a vasovagal reaction

(loss of consciousness), especially in patients prone to this reaction. Vasovagal reactions are characterized by hypotension, pallor, sweating, weakness, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, and in severe cases, loss of consciousness.

Vasovagal reactions can mimic anaphylaxis, as both conditions can involve hypotension and collapse. However, skin signs and symptoms are completely different. Fainting is usually preceded by pallor, while anaphylaxis often begins with flushing and may also include pruritus, urticaria, and angioedema. With anaphylaxis, tachycardia is more common than bradycardia. For patients who report a history of syncope in response to vaccinations, it is advisable to administer future vaccines in the supine position.

Routes of transmission of viral hepatitis B in adults

Blood is the main source of hepatitis B virus. It can also be found in other tissues and body fluids, but in lower concentrations.

The hepatitis B virus can be transmitted in several ways.

Through blood.

This may happen in the following cases:

- punctures of the skin with infected needles, lancets, scalpels or other sharp objects;

- direct contact with open sores of an infected person;

- splashes of infected blood on the skin with minor scratches, abrasions, burns or even minor rashes;

- splashes of blood on the mucous membranes of the mouth, nose or eyes;

- using other people's toothbrushes or razors.

Contact with surfaces contaminated with blood can also cause illness, but to a lesser extent.

By the way, the virus can remain stable in dried blood for up to 7 days at 25 °C.

Hand contact with blood-contaminated surfaces such as laboratory benches, test tubes, or laboratory instruments can transmit the virus to the skin or mucous membranes.

Through saliva.

The saliva of people with hepatitis B may contain the virus, but in very low concentrations compared to blood. Nevertheless, infection is possible, for example, through bites.

But it is impossible to become infected through dishes or mouthpieces (smoking or musical instruments) - such cases have not been registered.

Through semen or vaginal secretions.

Hepatitis B is found in semen and vaginal secretions. The virus can be transmitted during unprotected sex and from mother to child during childbirth.

Feces, nasal discharge, sputum, sweat, tears, urine, and vomit do not spread hepatitis B. Unless they are contaminated with blood, the risk of contracting hepatitis B from these fluids is very low.

Synovial fluid (lubricant for joints), amniotic fluid, cerebrospinal fluid, and peritoneal fluid (found in the abdomen) may contain hepatitis B virus, but the risk of transmission is unknown.

Hepatitis B is not spread by sneezing, coughing, shaking hands, hugging, kissing, breastfeeding, or sharing cutlery, water, or food.

Allergy to vaccine components

This phrase is listed as a contraindication in the instructions for medical use of many vaccines. But what exactly does it mean, what substances can we talk about? Important: the listed list is general for the vaccine industry, this does not mean that all listed substances and compounds are present in absolutely all vaccines; a specific list of excipients in each vaccine is reflected in its instructions for medical use.

Gelatin

. Added to many vaccines as a stabilizer, it can cause anaphylactic reactions to vaccines containing it. It is not uncommon for these individuals to be sensitized to alpha-gal (galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose), a carbohydrate allergen that causes mammalian meat allergy. Clinically significant allergies to beef and pork have been reported in some patients.

Before administering any gelatin-containing vaccine, a history of allergies to gelatin and gelatin-containing products (such as marshmallows and gummy candies) should be assessed. However, a negative allergy history does not exclude the possibility of anaphylaxis, so testing for gelatin allergy may be necessary.

Individuals who react to gelatin when taken by mouth should be evaluated by an allergist before receiving the vaccine. If there is a history of immediate allergic reaction to gelatin and this is confirmed by skin testing or serum IgE tests to gelatin, it is advisable to skin test such patients with gelatin-containing vaccines before administering them. If skin tests are negative for the vaccine, it can be administered as usual, but the patient must remain under observation for at least 30 minutes afterwards. If skin tests of the vaccine are positive, the vaccine can be administered in graduated doses. As an alternative, it is recommended to use gelatin-free vaccines if available.

The incidence of allergic reactions to gelatin in vaccines was particularly high in Japan, a phenomenon subsequently attributed in part to the genetic characteristics of the population. Japanese manufacturers have removed gelatin from some vaccines and switched to more thoroughly hydrolyzed gelatin in others, dramatically reducing the incidence of reactions. These strategies have been used differently in other countries, so reactions to gelatin in vaccines still occur.

Egg white

present in yellow fever, MMR, and some influenza and rabies vaccines. However, this amount is only potentially clinically significant in the yellow fever vaccine. MMR and rabies vaccines can be safely administered routinely to patients with egg allergies.

Before receiving the yellow fever vaccine, a history of allergies after eating eggs, raw or cooked, should be sought, and those with a positive history should be evaluated by an allergist. Such patients should undergo a skin test with yellow fever vaccine before administration. If skin tests for the vaccine are negative, the vaccine can be administered as usual, but the patient must remain under observation for at least 30 minutes afterwards. If skin tests of the vaccine are positive, the vaccine can be administered in graduated doses.

Cow's milk

. Casein, an allergenic protein found in cow's milk, has been previously implicated in anaphylaxis against diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (DTaP or Tdap) vaccines in a small number of children with severe milk allergy. Such vaccines are prepared in a medium derived from cow's milk protein, and nanogram amounts of residual casein have been demonstrated in these preparations. However, the vast majority of patients with severe milk allergies do not have allergic reactions to such vaccines.

Thimerosal, aluminum and phenoxyethanol

are added to some vaccines as preservatives, although the use of thimerosal (which contains mercury) in vaccines has been sharply reduced due to theoretical concerns about cumulative exposure to mercury in children. These preservatives have not been documented to cause immediate allergic reactions to vaccines, and immediate skin testing is not usually indicated.

Some antimicrobials

may be added in trace amounts to vaccines, most commonly neomycin, polymyxin B, and streptomycin. Although there are no specific reports of vaccine-induced anaphylaxis caused by these drugs, rare patients in whom anaphylactic reactions caused by these antibiotics have been documented should not receive vaccines containing them without first being evaluated by an allergist.

Latex

. The “rubber” in vaccine vial stoppers or syringe plungers can be either dry natural rubber (DNR) latex or synthetic rubber. Those made from latex pose a theoretical risk to patients with latex allergies, either as a result of the liquid vaccine solution drawing latex allergens out of the stopper upon physical contact, or as a result of the needle passing through the stopper and trapping the latex allergen inside or on the needle. One report of an anaphylactic reaction following administration of hepatitis B vaccine to a patient with latex allergy was associated with rubber in the stopper. A review of >160,000 reports from the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) identified only 28 cases of possible immediate-type allergic reactions after receiving a vaccine containing DNR, and these could have been caused by other components. The latex content in the vaccine packaging can be found in the instructions for medical use.

Patients with latex anaphylaxis can safely receive vaccines from stoppered vials without a DNR. If the only product available has a latex stopper, the stopper should be removed and the vaccine drawn directly from the vial without passing the needle through the stopper. If the only available vaccine contains latex in the package, which cannot be avoided, such as in a prefilled syringe, the vaccine can still be administered, but the patient should be observed for at least 30 minutes afterwards.

Unlike patients with latex-induced anaphylaxis, patients with contact latex allergies, such as hand dermatitis, can safely receive vaccines from vials with latex stoppers.

Yeast

. Some vaccines contain yeast protein, including hepatitis B vaccines (up to 25 mg per dose) and 4- and 9-valent human papillomavirus vaccines (<7 mcg per dose), but adverse reactions, if any, may occur. are rarely recorded. Yeast allergy itself is very rare, but if the patient has a history of clinical reactivity to baker's or brewer's yeast and a positive skin test for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, it would be advisable to perform a skin test before administering the vaccine. If the skin test is negative, the vaccine can be administered as usual, but the patient must be observed for at least 30 minutes afterwards. If skin tests are positive, the vaccine can be administered in graduated doses.

Dextran

causes allergic reactions to a specific brand of MMR vaccine previously used in Italy and Brazil. The reactions were associated with the presence of IgG to dextran, and the mechanism was suggested to be activation of the complement system and release of anaphylatoxin. This brand of vaccine has been withdrawn from the market, although dextran is found sporadically in other vaccines (for example, some rotavirus vaccines).

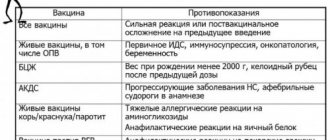

Problems of vaccination of children with allergic diseases

The only way to reduce the incidence of vaccine-preventable infections and prevent the development of epidemics at the present stage is 95% coverage of the population with preventive vaccinations. This means that not only healthy children, but also children suffering from various diseases are subject to vaccination.

The current opinion that vaccines are “allergenic” is valid only in relation to some of the substances they contain. Progress in the production of vaccines frees them to a greater extent from ballast substances: due to better purification, all vaccines included in the National Vaccination Calendar contain much less antigens than vaccines in the 20s and 30s. Both live and inactivated vaccines practically do not stimulate a persistent increase in IgE levels and the production of specific IgE antibodies.

The wide prevalence of allergic pathology in children, the annual increase in the number of patients in the pediatric population, the early onset, often in the first year of life, and the chronic nature of the disease have led to the fact that pediatricians constantly need to vaccinate children with allergic diseases. Currently, the attitude towards vaccination of children with allergy pathology has radically changed for the better. However, the lack of personal experience of practicing doctors, both in the tactics of treating such children and in approaches to carrying out preventive vaccinations for various forms and severity of the disease, puts the doctor in a difficult position when it comes to choosing vaccination tactics for these patients.

When deciding on the timing of vaccination, the volume of drug preparation and the choice of vaccine preparation, it is necessary to take into account the spectrum of sensitization, nosological form and stage of the disease, that is, the basis of the tactics of vaccinating children with allergic diseases is an individual approach to each child. However, despite the polymorphism of atopy manifestations, the immunization of these children is guided by a number of general principles:

- Children with allergic diseases are subject to vaccination against all infections included in the preventive vaccination calendar (tuberculosis, viral hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, polio, measles, mumps, rubella) in accordance with available instructions. Both domestic and foreign vaccine preparations are used for immunization. In this case, preference is given to combined vaccines (for example, measles-mumps divaccine or trivaccines (“Priorix”, “M-M-PII”) against measles, mumps and rubella), which allows to reduce the total volume of administered preservatives.

- In most cases, for children with allergic diseases, especially those with damage to the respiratory tract, it is advisable to expand the schedule of preventive vaccinations through annual vaccination against influenza, as well as against pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae infections. Vaccination against these infections leads not only to a reduction in the frequency and severity of intercurrent diseases, but also contributes to the positive dynamics of the course of the underlying disease, allowing for a reduction in the volume of basic therapy and an extension of the period of remission. The introduction of additional vaccine preparations can be combined with vaccines from the main vaccination schedule.

- A history of systemic allergic reactions to antibiotics contained in vaccines and to culture substrate antigens (in particular, chicken and/or quail egg white) in children with allergic diseases is a contraindication for the administration of measles and mumps vaccines. Identification of patients with a severe allergy to chicken egg proteins is also a contraindication for vaccination with influenza vaccines against tick-borne encephalitis prepared on a chicken substrate.

It is important to remember that the presence of a documented allergy to the listed components is not a clear contraindication to immunization with vaccines containing them; the nature of these reactions is also important. For example, if when trying to eat an egg, swelling of the lip or an anaphylactic reaction immediately occurs, then vaccination is absolutely contraindicated. If the allergy manifests itself as reactions of minor severity, then in most cases such patients can be vaccinated against the background of prophylactic administration of antiallergic drugs.

Severe allergic reactions to baker's yeast may be a contraindication for vaccination against viral hepatitis B, because yeast is used in the production of the main antigen and can be found in purely symbolic quantities in vaccines.

- Vaccination of children with allergic diseases is carried out when complete or partial remission is achieved; in the latter case, we are talking about the patient maintaining mild clinical manifestations without signs of exacerbation of the disease.

Children suffering from hay fever are given preventive vaccinations outside the dusting season of causally significant plants.

Vaccination of children with allergic diseases that are not seasonal is carried out at any time of the year, however, taking into account the epidemic situation, it is advisable to vaccinate children who often suffer from respiratory infections in warm years, outside the period of high incidence of acute respiratory viral infections (ARVI). The development of ARVI in one of the family members in a favorable epidemiological situation serves as the basis for a temporary (until their recovery) exemption from preventive vaccinations for children with allergic diseases.

According to epidemic indications, children with allergy pathology can be vaccinated during the period of exacerbation of the disease. In such cases, vaccination is carried out under the supervision of an allergist-immunologist.

- Preventive vaccinations for children with this pathology should be carried out against the background of basic therapy, the volume and duration of which depend on the period and severity of the allergic disease. It should be emphasized that long-term use of topical glucocorticosteroid drugs (inhaled, endonasal, conjunctival or cutaneous) is not a contraindication to the administration of vaccine drugs.

In all cases, one of the antimediator drugs is prescribed in an age-specific dosage for 3–5 days before and after vaccination, preference is given to 2nd and 3rd generation drugs. In the case of live vaccines (due to the later onset of adverse reactions), the use of antihistamines can continue for 2-3 weeks after vaccination.

- A high risk factor for the occurrence of severe manifestations of allergy to vaccine preparations is the development of systemic allergic reactions in the post-vaccination period in the form of generalized urticaria, Quincke's edema, and anaphylactic shock. Children who experience anaphylactic shock upon administration of the vaccine are subject to exclusion from subsequent immunization with this drug. The issue of continuing immunization of children who have systemic manifestations of allergies in the form of urticaria and allergic edema in the post-vaccination period is decided in each specific case individually, after consultation with an allergist. According to epidemiological indications, such children can be revaccinated during the period of remission of an allergic disease against the background of preventive antiallergic therapy, including parenteral administration of antihistamines, glucocorticosteroids, and adrenaline immediately before the vaccine is administered.

- Preventive vaccinations for children with allergic diseases should be carried out in immunization rooms, vaccination rooms, first aid stations (FAP) or in hospitals if anti-shock therapy is available. After each vaccination, the child should be under the supervision of medical personnel for at least 30 minutes, since during this period immediate systemic allergic reactions, which are the most dangerous for the patient, may develop.

- During the vaccination period, children are recommended to follow a diet excluding obligate allergens and histamine liberators (fish, eggs, honey, chocolate, nuts, cocoa, citrus fruits, strawberries, wild strawberries), and also refrain from taking other products to which allergic reactions have previously been noted, not including while introducing new foods into the diet. The diet is followed for at least 1 week before vaccination and 1–3 months after it (depending on the type of vaccine preparation and the course of the post-vaccination period).

- Skin tests with non-infectious and infectious allergens can be performed 1.5 weeks before the administration of vaccine preparations or 1-1.5 months after it.

- If a child receives a course of allergen-specific immunotherapy, as well as a course of therapy with Histaglobulin, Allergoglobulin or Antiallergic immunoglobulin, then vaccination should be carried out no earlier than 1–1.5 months after completion of the course of treatment, except in situations due to epidemiological indications. After the introduction of vaccine preparations, courses of therapy can be started no earlier than 1 month (with the introduction of live viral vaccines - after 1.5–2 months).

- After performing the Mantoux test, the administration of vaccine preparations (with the exception of BCG and BCG-M) is recommended no earlier than 10–12 days, since most children with allergic pathology have a positive reaction to tuberculin, indicating the presence of an allergic altered reactivity in the child, with For immunization due to epidemiological indications, this period may be shorter. After administration of the DTP vaccine, ADS, ADS-M toxoids, LCV (live measles vaccine) and mumps vaccine, the Mantoux test can be performed no earlier than 1.5 months later, i.e. period of recovery of immunological status indicators in children with allergic diseases.

- For children with an irregular vaccination schedule who have had a history of one vaccination with DPT vaccine or DPT, ADS-M toxoids, regardless of the time elapsed after it, it is enough to administer another dose of DTP or ADS-M toxoids, followed by revaccination after 6 months. The choice of vaccine depends on the age of the child. If children have a history of two vaccinations with DPT vaccine or ADS, ADS-M toxoid, revaccination with ADS or ADS-M toxoid should also be carried out without taking into account the time that has passed since the last vaccination, but not earlier than 6–12 months.

- The experience of vaccinating children with allergic diseases, which we have accumulated over many years of practice (from 1984 to the present) in the laboratory of vaccine prevention and immunotherapy of allergic diseases, State Research Institute of Vaccines and Serums named after. I.I. Mechnikov RAMS, indicates that immunization carried out during the period of complete remission of the disease in accordance with the above recommendations is practically not accompanied by post-vaccination complications or exacerbation of allergopathology.

A moderate exacerbation of the underlying disease was recorded only in patients with atopic dermatitis, in whom vaccination was carried out during unstable remission or during a subacute course. The frequency of exacerbation of atopic dermatitis was 8.6% after administration of the DPT vaccine, 10–21% after immunization with ADS-M toxoid, 4.5% after vaccination against measles and mumps. The immunization did not worsen the course of the allergic disease. Our experience has shown that such manifestations were short-lived and did not affect the course of the post-vaccination period during subsequent immunization.

Clinical observation of patients with bronchial asthma in the post-vaccination period showed that asthma attacks did not occur in any of the observed groups. A study of bronchial patency in 195 patients over 5 years of age during the full course of immunization with ADS-M toxoid confirmed that vaccination does not lead to an exacerbation of the underlying disease, even in the presence of obvious or hidden signs of bronchospasm. General mild and moderate reactions were recorded in 30 (14.5%) patients, mild allergic rashes in 10 (2.9%) patients, local infiltrates measuring 55 cm in 15 (4.4%) children, a combination of general and local reactions - in 10 (2.9%) cases. The probability of their occurrence did not depend on the duration of the remission period and corresponded to that during vaccination of healthy children with ADS-M toxoid. Therapy prescribed in the post-vaccination period, taking into account spirography data and the clinical picture, not only prevented the development of repeated attacks of asthma, but also, in some cases, contributed to the temporary normalization of bronchial patency. Thus, in patients who had signs of bronchial obstruction before vaccination, in the post-vaccination period the indicators of bronchial patency normalized and remained so for more than 6 months.

We vaccinated children against diphtheria and tetanus with a history of allergic urticaria and angioedema. Clinical observation carried out in the post-vaccination period for 6–12 months did not reveal a single case of recurrence of angioedema and urticaria, despite the fact that the duration of the period of remission of the disease at the time of vaccination varied from 1 week to 3 or more months.

When analyzing the reactions that occurred in children with allergic diseases within one month after the administration of the measles vaccine according to an individual regimen, it was possible to identify only a mild allergic rash in the first week after vaccination in 10.6% of those vaccinated for 4–5 days, and only in one The patient noted a moderate exacerbation of dermatitis within one week. Among children with bronchial asthma and hay fever, vaccination was not accompanied by exacerbation of the disease or the occurrence of any allergic reactions. Currently, there is evidence from additional studies confirming that vaccination against measles in children with bronchial asthma of any severity is safe and effective if carried out against the background of treatment of the underlying disease.

It is known that patients with allergies are more susceptible to tuberculosis, and among patients with tuberculosis, allergic pathology occurs 4 times more often than in people who are not sick. The combination of tuberculosis with bronchial asthma causes a particularly severe course of the latter. Thus, it is possible that anti-tuberculosis vaccination and revaccination are especially indicated for patients with asthma. For revaccination against tuberculosis in children suffering from allergic pathology, the BCG-M vaccine is used. Revaccination carried out during a period of stable remission of the allergic process is not accompanied by an exacerbation of the underlying disease. The BCG-M vaccine, in addition to its specific protective effect, has a pronounced immunomodeling effect, which, in turn, helps reduce the incidence of intercurrent acute respiratory viral infections and associated exacerbations of bronchial asthma.

A full course of vaccination against hepatitis B was administered to 40% of children with atopic dermatitis, 30% with bronchial asthma, 20% with seasonal and year-round allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, 10% with urticaria and Quincke's edema with varying severity of the underlying disease against the background of basic therapy. In the post-vaccination period, no unusual reactions or complications, including exacerbation of the underlying disease, were observed.

Children with allergic diseases, especially those suffering from bronchial asthma, need protection from acute respiratory infections, incl. flu According to WHO recommendations, all patients with bronchial asthma should be vaccinated against influenza annually, regardless of the form and severity of the disease or drug therapy. We did not detect repeated asthma attacks in the post-vaccination period or the occurrence of other reactions during influenza vaccination. Studies have not demonstrated deterioration in respiratory function, increased asthma symptoms, or increased use of drug therapy. Local reactions (in the form of pain at the site of vaccine administration) and a general mild reaction (fever up to 37–37.2°C) were detected in 10% of cases, and no drug treatment was required. In 2% of cases, an allergic rash developed, which quickly disappeared with the use of Claritin. When observing children for 6 months after vaccination, ARVI was noted in 5% of cases (serological identification was not carried out). For comparison, during the same period of time before vaccination, children suffered from ARVI 3-6 times a year.

The most effective in children with bronchial asthma was the combined use of vaccines against influenza and pneumococcal infection. When vaccinating children with varying severity of bronchial asthma with Vaxigrip and Pneumo 23, there was a decrease in the frequency of exacerbations of the disease by 1.7 times, the number of intercurrent respiratory infections by 2.5 times, and an improvement in external respiratory function indicators (FEV1, SOS25–75 and SOS75–85). At the same time, in the dynamics of the vaccination process, no changes in the content of eosinophils in the peripheral blood and the results of skin prick tests were detected.

Vaccination against meningococcal infection of serogroups A+C is recommended by us to all children after completing the full course of vaccination, according to the national vaccination schedule. As a rule, this coincides with the child’s entry into kindergarten and, less often, school. We observed more than 120 children of various ages (over two years old) with various allergic diseases. Vaccination was carried out with the drug “Polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine A+C” during the period of remission of the disease and, as always, against the background of a short course of antimediator drugs. In the clinical aspect, the introduction of the Polysaccharide meningococcal vaccine A+C, like any other polysaccharide vaccine, was accompanied by the occurrence of mild local reactions (no more than 3–4% of cases) and almost the same frequency of general mild temperature reactions. Allergic diseases did not worsen due to vaccination.

It is characteristic that the concentration of total IgE in the post-vaccination period increased briefly and after 1.5–2 months returned to the original values. A transient increase in the level of total IgE was observed mainly in children who had general or local allergic reactions in the post-vaccination period.

The administration of vaccine preparations to children with allergic diseases is accompanied by the synthesis of antibodies to vaccine antigens at the level of protective values, as in healthy children.

Thus, the studies not only confirm the possibility, but also indicate the need for active immunization of children with allergy pathology. Allergic diseases are an indication for vaccination rather than a contraindication, since in these children the infections are especially severe (for example, whooping cough in a patient with asthma). A pediatrician, when consulting such a child with an allergist, should raise the question not about the admissibility of vaccinations, but about choosing the optimal time for their implementation and the need for medicinal protection (antihistamines for cutaneous forms of atopy, inhaled steroids and beta-agonists for asthma).

It should be emphasized that neither the presence of allergic pathology, nor the development of post-vaccination reactions or exacerbation of an allergic disease after the administration of vaccine preparations is an absolute contraindication to future preventive vaccinations.

Literature

- Medunitsin N.V. Vaccinology. M.: Triad-H. 1999. 272 p.

- Fundamentals of vaccine prevention in children with chronic pathology / Ed. M.P. Kostinova. M.: Medicine for everyone. 2002. 320 p.

- Martishevskaya E.A. Clinical and immunological characteristics of the measles vaccine process in children with bronchial asthma. Author's abstract. Ph.D. honey. Sci. St. Petersburg 2001. 22 p.

- Pukhlik B.M. The relationship between tuberculosis and allergic diseases // Probl. tuberk. 1983. No. 11. pp. 29–32.

- Ala'Eldin H., Ahmed A., Karl G. et al. Influenza vaccination in patients with asthma: effect on peak expiratory flow, asthma symptoms and use of medication. Vaccine 1997; 15:1008–1009.

- Markova T.P., Chuvirov D.G. The use of the Influvac vaccine for the prevention of influenza in children with allergic diseases // Russian Bulletin of Perenatology and Pediatrics. 2001.

- Karpocheva S.V., Andreeva N.P., Magarshak O.O. and others. The course of bronchial asthma and “Vaxigrip” // XIII Russian National Congress “Man and Medicine”: Abstracts of reports. M. 2006. P. 534.

- Guidelines No. 3.3.1.1095-02. Medical contraindications to preventive vaccinations with drugs from the national vaccination calendar.

O. O. Magarshak , Candidate of Medical Sciences M. P. Kostinov , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the Research Institute of Vaccines and Serums named after. AND.

and Mechnikov RAMS , Moscow

Source: TREATING DOCTOR

Can a person with allergies be given the vaccine?

The diagnostic approach is different for a patient who has reacted to a vaccine component such as gelatin, eggs, latex or yeast, but not to the active substance itself. The following situation often occurs: flu vaccination of a patient with an egg allergy, which proceeds successfully and without complications.

What clinical questions should be answered before vaccinating a patient with an allergy?

- Are the nature of the manifestations and timing of onset consistent with anaphylaxis? Does this sound like an IgE-mediated clinical picture?

- Do you have a history of a similar reaction? It is important to obtain this information and determine whether it was caused by the vaccine's antigenic material or excipients. The various components of the vaccine are clearly listed in the instructions for use supplied by the manufacturers. If the reaction occurs after the first dose of the vaccine, the likelihood that the immunizing agent itself is an allergen is greatly reduced. In this clinical situation, healthcare providers should also inquire about allergic reactions to food, especially gelatin.

- Is there a need for future doses of this vaccine or other vaccines with common components? Following a history of a vaccine reaction occurring shortly after administration that is consistent with an IgE-mediated reaction, the clinician should determine whether future doses of the suspected vaccine or other vaccines with common components are required. Given the potential for cross-reaction with common components in other vaccines and with foods, careful evaluation is warranted even if additional doses of the potentially allergenic vaccine are not required.

How to diagnose vaccine allergy?

If the patient is to receive additional doses of the vaccine, skin testing using that same vaccine must be performed. Correct performance and interpretation of skin testing requires experience in the procedure, including the use of appropriate positive and negative controls. In addition, skin testing itself can rarely cause anaphylactic reactions in people with severe allergies. Therefore, skin testing should be performed only by individuals, such as allergists, who are trained in the interpretation and management of possible reactions to the tests, and only in settings where anaphylactic reactions can be recognized and promptly managed.

The vaccine must first be tested by skin prick testing. The full-strength vaccine can be used if the history of the reaction was not truly life-threatening; in this case, it is advisable to dilute the vaccine before the skin injection.

If the full prick test is negative, an intradermal test should be performed with vaccine diluted 1:100 in 0.9 percent (isotonic) saline, again with appropriate positive and negative controls.

Interpretation of skin tests for vaccines. Allergy history is critical to the interpretation of vaccine skin tests. Clinically irrelevant positive skin tests are possible, as with skin testing for any allergen. The presence of a positive vaccine skin test does not necessarily indicate a subsequent reaction, although it should be considered a significant risk factor.

Vaccines may induce IgE production in the first days or weeks after vaccination, although the clinical significance of this is unclear. Specific IgE to diphtheria (DT) and tetanus toxoids has been induced by vaccination and has been found to persist for at least two years after immunization. This specific IgE was not associated with allergic reactions following subsequent vaccination.

Irritant (false-positive) reactions to skin tests are also possible, especially with intradermal tests at concentrations of 1:10 or undiluted. One study of 20 adult volunteers with no history of vaccine reactions assessed reactions to skin prick and intradermal testing with 10 common vaccines. Irritant reactions were not observed in skin prick testing and were uncommon following intradermal testing at a 1:100 concentration. However, they were common at higher intradermal concentrations (1:10 or undiluted). Therefore, intradermal testing of vaccines should only be performed at a concentration of 1:100.

Delayed reactions. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions have been observed at the site of skin testing (especially intradermal testing) with the vaccine. These reactions are not relevant to the diagnosis of IgE-mediated vaccine allergy.

Testing of vaccine components. If the suspected vaccine contains eggs, gelatin, latex, or Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast, the patient should also undergo skin testing for the following:

Skin pricks:

- Extracts of eggs and yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae for skin testing.

- Gelatin extract can be prepared by dissolving 1 teaspoon of candied gelatin powder of any color or flavor in 5 ml of saline to create a skin test solution.

- Standardized natural rubber latex (NRL) extracts.

Measurement of allergen-specific IgE in serum:

- Specific IgE to eggs, gelatin, latex and yeast can be measured in serum using immunoassays. The sensitivity of the ImmunoCAP and Immulite latex tests is approximately 80%.

Treatment of acute allergic conditions at the prehospital stage

Acute allergic diseases include anaphylactic shock, exacerbation (attack) of bronchial asthma, acute laryngeal stenosis, Quincke's edema, urticaria, exacerbation of allergic conjunctivitis and/or allergic rhinitis. It is believed that on average about 10% of the world's population suffers from allergic diseases. Of particular concern are the data from the NNPO emergency medical services, according to which over the past 3 years the number of calls for acute allergic diseases in the Russian Federation as a whole has increased by 18%.

Main causes and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of allergic reactions today has been quite fully studied and described in detail in many domestic and foreign monographs on allergology and clinical immunology. The central role in the implementation of immunopathological reactions belongs to class E immunoglobulins (IgE), the binding of which to the antigen leads to the release of allergy mediators (histamine, serotonin, cytokines, etc.) from mast cells.

Most often, allergic reactions develop when exposed to inhalant allergens in homes, epidermal, pollen, food allergens, medications, parasite antigens, as well as insect bites. Drug allergies most often develop when using analgesics, sulfonamides and antibiotics from the penicillin group, less often cephalosporins (the risk of cross-sensitization to penicillin and cephalosporins, which ranges from 2 to 25%), should be taken into account. In addition, the number of cases of latex allergies has now increased.

Clinical picture, classification and diagnostic criteria

From the point of view of determining the volume of necessary drug therapy at the prehospital stage of care and assessing the prognosis, acute allergic diseases can be divided into mild (allergic rhinitis - year-round or seasonal, allergic conjunctivitis - year-round or seasonal, urticaria), moderate and severe (generalized urticaria, edema Quincke's disease, acute laryngeal stenosis, moderate exacerbation of bronchial asthma, anaphylactic shock). The classification and clinical picture of acute allergic diseases are presented in Table. 1.

When analyzing the clinical picture of an allergic reaction, the emergency physician should receive answers to the following questions (Table 2).

The initial prehospital assessment should assess for stridor, dyspnea, wheezing, dyspnea, or apnea; hypotension or syncope; changes on the skin (rashes such as urticaria, Quincke's edema, hyperemia, itching); gastrointestinal manifestations (nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea); changes in consciousness. If a patient experiences stridor, severe dyspnea, hypotension, arrhythmia, convulsions, loss of consciousness, or shock, the condition is considered life-threatening.

Treatment of acute allergic diseases

In case of acute allergic diseases at the prehospital stage, emergency therapy is based on the following areas:

Stopping further entry of the suspected allergen into the body.

For example, in case of a reaction to a drug administered parenterally, or in case of insect bites, apply a tourniquet above the injection site (or bite) for 25 minutes (every 10 minutes it is necessary to loosen the tourniquet for 1-2 minutes); Ice or a heating pad with cold water is applied to the injection or bite site for 15 minutes; pricking at 5-6 points and infiltrating the injection site or bite with 0.3-0.5 ml of a 0.1% solution of adrenaline with 4.5 ml of isotonic sodium chloride solution.

Antiallergic therapy (antihistamines or glucocorticosteroids).

The administration of antihistamines (H1-histamine receptor blockers) is indicated for allergic rhinitis, allergic conjunctivitis, and urticaria. There are classic antihistamines (for example, suprastin, diphenhydramine) and new generation drugs (semprex, telfast, clarotadine, etc.). It should be noted that classical antihistamines, in contrast to new generation drugs, are characterized by a short exposure time with a relatively rapid onset of clinical effect; many of these drugs are available in parenteral forms. New generation antihistamines are devoid of cardiotoxic effects, have a competitive effect on histamine, are not metabolized by the liver (for example, the pharmacokinetics of Semprex does not change even in patients with impaired liver and kidney function) and do not cause tachyphylaxis. These drugs have a long-lasting effect and are intended for oral administration.

For anaphylactic shock and angioedema (in the latter case, the drug of choice), prednisolone is administered intravenously (adults - 60-150 mg, children - at the rate of 2 mg per 1 kg of body weight). For generalized urticaria or when urticaria is combined with Quincke's edema, betamethasone (diprospan in a dose of 1-2 ml intramuscularly), consisting of disodium phosphate (provides a rapid effect) and betamethasone dipropionate (provides a prolonged effect), is highly effective. For the treatment of bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, and allergic conjunctivitis, topical forms of glucocorticosteroids (fluticasone, budesonide) have been developed. In case of Quincke's edema, to prevent the effect of histamine on tissues, it is necessary to combine new generation antihistamines (Semprex, Claritin, Clarotadine) with glucocorticosteroids (GCS).

Side effects of systemic corticosteroids are arterial hypertension, increased agitation, arrhythmia, ulcerative bleeding. Side effects of topical corticosteroids include hoarseness, microflora disturbance with further development of mucosal candidiasis; when using high doses, skin atrophy, gynecomastia, weight gain, etc. Contraindications: peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum, severe arterial hypertension, renal failure , history of hypersensitivity to glucocorticoids.

Symptomatic therapy.

With the development of bronchospasm, inhaled administration of b2-agonists and other bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory drugs (Berodual, Atrovent, Ventolin, Pulmicort) through a nebulizer is indicated. Correction of arterial hypotension and replenishment of circulating blood volume is carried out by administering saline and colloid solutions (isotonic sodium chloride solution - 500-1000 ml, stabizol - 500 ml, polyglucin - 400 ml). The use of vasopressor amines (dopamine - 400 mg per 500 ml of 5% glucose, norepinephrine - 0.2-2 ml per 500 ml of 5% glucose solution, the dose is titrated until a systolic pressure level of 90 mm Hg is achieved) is possible only after replenishment of the bcc. For bradycardia, atropine can be administered at a dose of 0.3-0.5 mg subcutaneously (if necessary, the injection is repeated every 10 minutes). In the presence of cyanosis, dyspnea, and dry wheezing, oxygen therapy is also indicated.

Anti-shock measures (see picture).

In case of anaphylactic shock, the patient should be laid down (head lower than legs), head turned to the side (to avoid aspiration of vomit), and the lower jaw should be extended (if there are removable dentures, they should be removed).

Adrenaline is administered subcutaneously in a dose of 0.1-0.5 ml of a 0.1% solution (drug of choice); if necessary, injections are repeated every 20 minutes for an hour under blood pressure monitoring. In case of unstable hemodynamics with the development of an immediate threat to life, intravenous administration of adrenaline is possible. In this case, 1 ml of a 0.1% solution of adrenaline is diluted in 100 ml of isotonic sodium chloride solution and administered at an initial rate of 1 mcg/min (1 ml per minute). If necessary, the speed can be increased to 2-10 mcg/min. Intravenous administration of adrenaline is carried out under the control of heart rate, respiration, and blood pressure levels (systolic blood pressure must be maintained at a level of more than 100 mm Hg in adults and more than 50 mm Hg in children).

Side effects of adrenaline include dizziness, tremors, weakness; strong heartbeat, tachycardia, various arrhythmias (including ventricular), the appearance of pain in the heart area; difficulty breathing; increased sweating; excessive increase in blood pressure; urinary retention in men suffering from prostate adenoma; increased blood sugar levels in patients with diabetes. Cases of the development of tissue necrosis with repeated subcutaneous injection of adrenaline into the same place due to local vasoconstriction have also been described. Contraindications: arterial hypertension; severe cerebral atherosclerosis or organic brain damage; cardiac ischemia; hyperthyroidism; angle-closure glaucoma; diabetes; prostatic hypertrophy; non-anaphylactic shock; pregnancy. However, even with these diseases, it is possible to prescribe adrenaline for anaphylactic shock for health reasons and under strict medical supervision.

Typical mistakes made at the prehospital stage

The isolated prescription of H1-histamine blockers for severe allergic reactions, as well as for broncho-obstructive syndrome, has no independent significance, and at the prehospital stage it only leads to an unjustified loss of time; the use of diprazine (pipolfen) is dangerous by worsening hypotension. The use of drugs such as calcium gluconate and calcium chloride is generally not indicated for acute allergic diseases. Late prescription of GCS, unreasonable use of small doses of GCS, refusal to use topical GCS and b2-agonists for allergic laryngeal stenosis and bronchospasm should also be considered erroneous.

Indications for hospitalization

Patients with severe allergic diseases must be hospitalized.

A. L. Vertkin, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor A. V. Topolyansky, Candidate of Medical Sciences

Procedure for vaccinating patients with vaccine allergies

Most patients with previous reactions to vaccines can be vaccinated safely in the future with appropriate precautions.

General strategy: If the vaccine intradermal test is negative, then the likelihood that the patient has IgE to either vaccine is negligible and the vaccine can be administered in the usual manner. However, it is prudent to observe such patients for at least 30 minutes and have a bed in close proximity to assist with anaphylactic shock.

If skin tests of a vaccine or vaccine component are positive, and if the vaccine is considered necessary, it can still be administered using a graduated-dose protocol. Successful administration of vaccines to patients with positive skin tests using graded protocols has been described for several different vaccines.

Administration of the vaccine to an allergic person, even with this graded-dose protocol, still carries the risk of an anaphylactic reaction and should only be done after written informed consent has been obtained. In addition, administration should be done in a setting where personnel and equipment are available to recognize and treat anaphylaxis.

Bibliography

- Johansson SG, Bieber T, Dahl R, et al. Revised nomenclature for allergy for global use: Report of the Nomenclature Review Committee of the World Allergy Organization, October 2003 // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 113:832.

- Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117:391.

- Bohlke K, Davis RL, Marcy SM, et al. Risk of anaphylaxis after vaccination of children and adolescents // Pediatrics 2003; 112:815.

- McNeil MM, Weintraub ES, Duffy J, et al. Risk of anaphylaxis after vaccination in children and adults // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137:868.

- Patja A, Mäkinen-Kiljunen S, Davidkin I, et al. Allergic reactions to meats-mumps-rubella vaccination // Pediatrics 2001; 107:E27.

- Cheng DR, Perrett KP, Choo S, et al. Pediatric anaphylactic adverse events following immunization in Victoria, Australia from 2007 to 2013 // Vaccine 2015; 33:1602.

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. General recommendations on immunization - recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) // MMWR Recomm Rep 2011; 60:1.

- Broder KR, Cortese MM, Iskander JK, et al. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) // MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1.

- Kretsinger K, Broder KR, Cortese MM, et al. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adults: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and recommendation of ACIP, supported by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) , for use of Tdap among health-care personnel // MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1.

- Talbot EA, Brown KH, Kirkland KB, et al. The safety of immunizing with tetanus-diphtheria-cellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) less than 2 years following previous tetanus vaccination: Experience during a mass vaccination campaign of healthcare personnel during a respiratory illness outbreak // Vaccine 2010; 28:8001.

- Beytout J, Launay O, Guiso N, et al. Safety of Tdap-IPV given one month after Td-IPV booster in healthy young adults: a placebo-controlled trial // Hum Vaccin 2009; 5:315.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010 // MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011; 60:13.

- Bergfors E, Trollfors B. Sixty-four children with persistent itching nodules and contact allergy to aluminum after vaccination with aluminum-adsorbed vaccines-prognosis and outcome after booster vaccination // Eur J Pediatr 2013; 172:171.

- Kang LW, Crawford N, Tang ML, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to human papillomavirus vaccine in Australian schoolgirls: retrospective cohort study // BMJ 2008; 337:a2642.

- Kelso JM, Greenhawt MJ. Adverse reactions to vaccines in infectious diseases. In: Middleton's allergy: Principles and practice, 8th ed, Adkinson NF, Bochner BS, Burks AW, et al (Eds), Elsevier, Philadelphia 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Syncope after vaccination—United States, January 2005-July 2007 // MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2008; 57:457.

- Kelso JM, Jones RT, Yunginger JW. Anaphylaxis to measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine mediated by IgE to gelatin // J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993; 91:867.

- Sakaguchi M, Nakayama T, Inouye S. Food allergy to gelatin in children with systemic immediate-type reactions, including anaphylaxis, to vaccines // J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996; 98:1058.

- Sakaguchi M, Yamanaka T, Ikeda K, et al. IgE-mediated systemic reactions to gelatin included in the varicella vaccine // J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997; 99:263.

- Sakaguchi M, Miyazawa H, Inouye S. Specific IgE and IgG to gelatin in children with systemic cutaneous reactions to Japanese encephalitis vaccines // Allergy 2001; 56:536.

- Lasley MV. Anaphylaxis after booster influenza vaccine due to gelatin allergy // Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol 2007; 20:201.

- Stone CA Jr, Hemler JA, Commins SP, et al. Anaphylaxis after zoster vaccine: Implicating alpha-gal allergy as a possible mechanism // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:1710.

- Kumagai T, Yamanaka T, Wataya Y, et al. A strong association between HLA-DR9 and gelatin allergy in the Japanese population // Vaccine 2001; 19:3273.

- Sakaguchi M, Nakayama T, Kaku H, et al. Analysis of HLA in children with gelatin allergy // Tissue Antigens 2002; 59:412.

- Kuno-Sakai H, Kimura M. Removal of gelatin from live vaccines and DTaP-an ultimate solution for vaccine-related gelatin allergy // Biologicals 2003; 31:245.

- O'Brien TC, Maloney CJ, Tauraso NM. Quantitation of residual host protein in chicken embryo-derived vaccines by radial immunodiffusion // Appl Microbiol 1971; 21:780.

- Kelso JM. Raw egg allergy-a potential issue in vaccine allergy // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106:990.

- Kattan JD, Konstantinou GN, Cox AL, et al. Anaphylaxis to diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines among children with cow's milk allergy // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:215.

- Grabenstein JD. Clinical management of hypersensitivities to vaccine components // Hosp Pharm 1997; 32:77.

- Heidary N, Cohen DE. Hypersensitivity reactions to vaccine components // Dermatitis 2005; 16:115.

- Patrizi A, Rizzoli L, Vincenzi C, et al. Sensitization to thimerosal in atopic children // Contact Dermatitis 1999; 40:94.

- Lee-Wong M, Resnick D, Chong K. A generalized reaction to thimerosal from an influenza vaccine // Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 94:90.

- Audicana MT, Muñoz D, del Pozo MD, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from mercury antiseptics and derivatives: study protocol of tolerance to intramuscular injections of thimerosal // Am J Contact Dermat 2002; 13:3.

- Lear JT, English JS. Anaphylaxis after hepatitis B vaccination // Lancet 1995; 345:1249.

- Russell M, Pool V, Kelso JM, Tomazic-Jezic VJ. Vaccination of persons allergic to latex: a review of safety data in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) // Vaccine 2004; 23:664.

- Hamilton RG, Brown RH, Veltri MA, et al. Administering pharmaceuticals to latex-allergic patients from vials containing natural rubber latex closures // Am J Health Syst Pharm 2005; 62:1822.

- DiMiceli L, Pool V, Kelso JM, et al. Vaccination of yeast sensitive individuals: review of safety data in the US vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS) // Vaccine 2006; 24:703.

- Zanoni G, Puccetti A, Dolcino M, et al. Dextran-specific IgG response in hypersensitivity reactions to meats-mumps-rubella vaccine // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122:1233.

- Martín-Muñoz MF, Pereira MJ, Posadas S, et al. Anaphylactic reaction to diphtheria-tetanus vaccine in a child: specific IgE/IgG determinations and cross-reactivity studies // Vaccine 2002; 20:3409.

- Skov PS, Pelck I, Ebbesen F, Poulsen LK. Hypersensitivity to the diphtheria component in the Di-Te-Pol vaccine. A type I allergic reaction demonstrated by basophil histamine release // Pediatr Allergy Immunol 1997; 8:156.

- Bégin P, Vu MQ, Picard M, et al. Spontaneous resolution of diphtheria-tetanus vaccine hypersensitivity in a pediatric population // Allergy 2011; 66:1508.

- Systemic adverse effects of hepatitis B vaccines are rare // Prescrire Int 2004; 13:218.

- Nelson MR, Oaks H, Smith LJ, et al. Anaphylaxis complicating routine childhood immunization: Hemophilus Influenza b conjugated vaccine // Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol 2000; 14:315.

- Brotherton JM, Gold MS, Kemp AS, et al. Anaphylaxis following quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccination // CMAJ 2008; 179:525.

- Nagao M, Fujisawa T, Ihara T, Kino Y. Highly increased levels of IgE antibodies to vaccine components in children with influenza vaccine-associated anaphylaxis // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137:861.

- Takahashi H, Pool V, Tsai TF, Chen RT. Adverse events after Japanese encephalitis vaccination: review of post-marketing surveillance data from Japan and the United States. The VAERS Working Group // Vaccine 2000; 18:2963.

- James JM, Burks AW, Roberson PK, Sampson HA. Safe administration of the meats vaccine to children allergic to eggs // N Engl J Med 1995; 332:1262.

- Ball R, Braun MM, Mootrey GT, Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System Working Group. Safety data on meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System // Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:1273.

- Ponvert C, Ardelean-Jaby D, Colin-Gorski AM, et al. Anaphylaxis to the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine in child: a case-control study based on immediate responses in skin tests and specific IgE determination // Vaccine 2001; 19:4588.

- Ponvert C, Scheinmann P, de Blic J. Anaphylaxis to the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine: a second explored case by means of immediate-reading skin tests with pneumococcal vaccines // Vaccine 2010; 28:8256.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Systemic allergic reactions following immunization with human diploid cell rabies vaccine // MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1984; 33:185.

- Swanson MC, Rosanoff E, Gurwith M, et al. IgE and IgG antibodies to beta-propiolactone and human serum albumin associated with urticarial reactions to rabies vaccine // J Infect Dis 1987; 155:909.

- Carey AB, Meltzer EO. Diagnosis and “desensitization” in tetanus vaccine hypersensitivity // Ann Allergy 1992; 69:336.

- Mayorga C, Torres MJ, Corzo JL, et al. Immediate allergy to tetanus toxoid vaccine: determination of immunoglobulin E and immunoglobulin G antibodies to allergenic proteins // Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2003; 90:238.

- Slater JE, Rabin RL, Martin D. Comments on cow's milk allergy and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128:434; author reply 435.

- Begier EM, Burwen DR, Haber P, et al. Postmarketing safety surveillance for typhoid fever vaccines from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, July 1990 through June 2002 // Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38:771.

- Hoyt RE, Herip DS. Severe systemic reactions attributed to the acetone-inactivated parenteral typhoid vaccine // Mil Med 1996; 161:339.

- Wise RP, Salive ME, Braun MM, et al. Postlicensure safety surveillance for varicella vaccine // JAMA 2000; 284:1271.

- Kelso JM, Mootrey GT, Tsai TF. Anaphylaxis from yellow fever vaccine // J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103:698.

- Tseng HF, Liu A, Sy L, et al. Safety of zoster vaccine in adults from a large managed-care cohort: a Vaccine Safety Datalink study // J Intern Med 2012; 271:510.

- Kelso JM, Greenhawt MJ, Li JT, et al. Adverse reactions to vaccines practice parameter 2012 update // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130:25.

- Mark A, Björkstén B, Granström M. Immunoglobulin E responses to diphtheria and tetanus toxoids after booster with aluminum-adsorbed and fluid DT-vaccines // Vaccine 1995; 13:669.

- Aalberse RC, van Ree R, Danneman A, Wahn U. IgE antibodies to tetanus toxoid in relation to atopy // Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1995; 107:169.

- Wood RA, Setse R, Halsey N, Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network Hypersensitivity Working Group. Irritant skin test reactions to common vaccines // J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120:478.

- Bierman CW, Shapiro GG, Pierson WE, et al. Safety of influenza vaccination in allergic children // J Infect Dis 1977; 136 Suppl:S652.

- Miller JR, Orgel HA, Meltzer EO. The safety of egg-containing vaccines for egg-allergic patients // J Allergy Clin Immunol 1983; 71:568.

- Kelso JM, Cockrell GE, Helm RM, Burks AW. Common allergens in avian meats // J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 104:202.